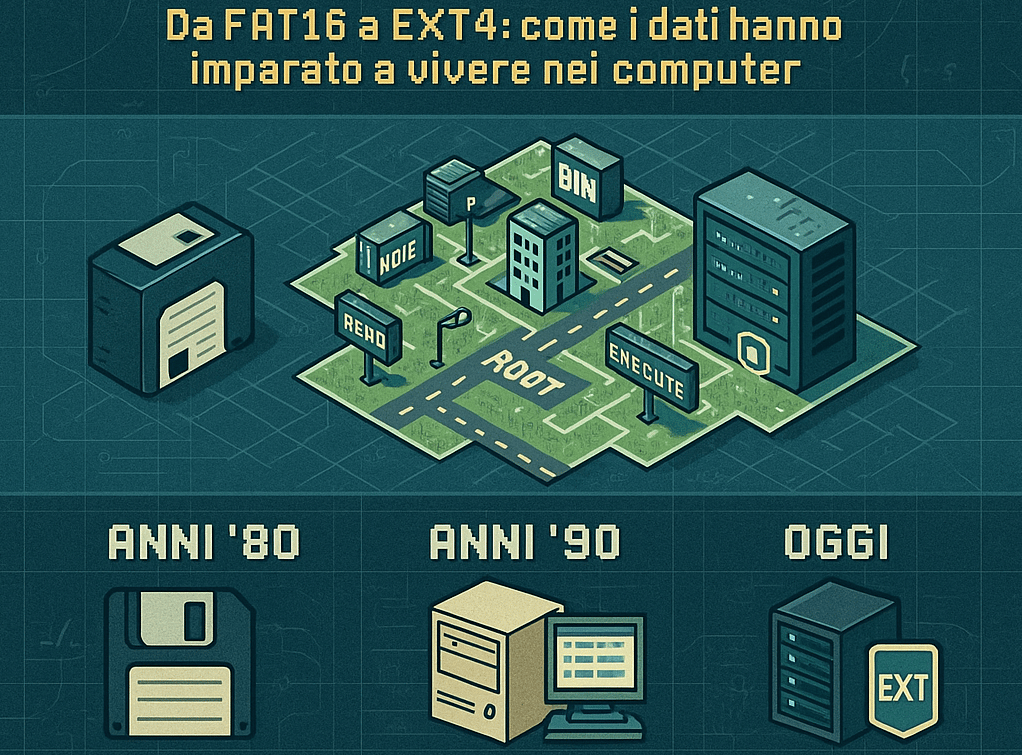

The History of File Systems

A Journey into the Invisible Foundations of the Digital World

FIRST PAGEDIGITAL CULTURE AND PHILOSOPHY

The History of File Systems:

A Journey into the Invisible Foundations of the Digital World

How the evolution of data storage has shaped modern computing

Preface:

The Silent Guardians of Our Data

There's a fascinating paradox in the world of computing: the most important technologies are often the ones we notice the least. File systems belong to this category. Every time you save a document, copy a photo, or simply turn on your computer, a sophisticated organizational system works in the shadows, translating your commands into sequences of bits arranged on magnetic, optical, or solid-state media.

Imagine an infinite library, with billions of books in constant motion. Every book must be catalogued, every page must be retrievable in fractions of a second, and the entire structure must withstand power outages, hardware failures, and even human errors. This is what a file system does: it transforms binary chaos into comprehensible order.

But how did we get here? How has the way computers organize data evolved, from the first floppy disks to modern data centers that store petabytes of information? This is the story of file systems: a journey through decades of innovation, spectacular failures, silent revolutions, and brilliant insights that have shaped the digital world as we know it.

1. Introduction: Why Should You Care?

1.1 The Historical Context

To understand the importance of file systems, we need to step back and observe the evolution of digital storage as a whole.

In the 1950s and '60s, the first computers didn't have the luxury of hard drives or accessible permanent memory. Data was entered through punched cards and magnetic tapes, in a slow and laborious process. There was no concept of "file" as we understand it today: there were only sequences of data to be processed sequentially.

The advent of magnetic disks in the 1960s changed everything. For the first time, it was possible to access data randomly, jumping from one position on the disk to another without having to read everything that came before. But this new freedom brought a problem: how to organize this data efficiently?

Thus were born the first file systems, organizational systems that had to solve fundamental problems:

How to know where a file begins and ends?

How to quickly find a file among thousands?

How to manage free space on the disk?

How to protect data from corruption?

1.2 Analysis Objectives

This article aims to explore the evolution of file systems from several perspectives:

Historical: How we went from floppy disks to modern enterprise systems

Technical: The fundamental principles that govern data organization

Practical: Which file system to choose for each situation

Prospective: Where innovation in this field is heading

Whether you're a technology enthusiast, a system administrator, or simply someone who wants to better understand what happens "under the hood" of your computer, you'll find something interesting in this journey.

1.3 Article Structure

The analysis is divided into several sections:

The origins: FAT and the floppy disk era

Maturity: NTFS, ext and HFS+ in the 2000s

The revolution: ZFS and the new paradigm of data integrity

The present: exFAT, Btrfs, APFS and modern solutions

Practical guide: Which file system for which situation

The future: Emerging trends and innovations

2. The Origins: The FAT Era and the Birth of Digital Organization

2.1 The Context: When Computers Were Dinosaurs

It's the late 1970s. Personal computers are being born, but they are primitive machines by today's standards. The Apple II has just debuted, the IBM PC is yet to come, and memory is measured in kilobytes, not gigabytes.

In this scenario, Microsoft is developing an operating system for the first microcomputers. There's a fundamental problem to solve: how to organize data on the 5.25-inch floppy disks that are becoming the standard for software distribution?

The answer was FAT (File Allocation Table), an organizational system elegant in its simplicity.

2.2 FAT: The Architecture of a Silent Revolution

The name itself tells the system's philosophy: at the center of everything is a "file allocation table," a sort of index that keeps track of where data is stored on the disk.

Imagine the disk as a large grid notebook. Each square (called a "cluster") can contain a certain amount of data. The FAT is like an index at the beginning of the notebook that says: "The file DOCUMENT.TXT starts at square 15, continues to 16, then jumps to 45, and ends at 46."

This system had several advantages for its time:

Simplicity: Easy to implement with the limited hardware resources of the time

Efficiency: Random file access was relatively fast

Compatibility: Could work on very different hardware

Robustness: A backup copy of the FAT protected against the most common failures

2.3 The Evolution of the FAT Species

Like any successful technology, FAT evolved over time to adapt to increasingly capacious storage media:

FAT12 (1977-1980)

The original version, designed for floppy disks. The "12" indicates that each entry in the table used 12 bits, allowing up to 4,096 clusters to be addressed. With reasonably sized clusters for the era, this was sufficient for disks up to about 16 MB.

Main characteristics:

Designed for floppies from 160 KB to 16 MB

File names in 8.3 format (eight characters for the name, three for the extension)

No support for permissions or advanced attributes

Still used today in some embedded applications

FAT16 (1984-1987)

With the arrival of the first hard disks for personal computers, a system was needed that could handle larger capacities. FAT16 extended the table to 16 bits per entry, allowing up to 65,536 clusters.

Main characteristics:

Support for volumes up to 2 GB (with 32 KB clusters)

Still the 8.3 format for file names

Became the standard for MS-DOS and early versions of Windows

Efficiency problems with large disks (too large clusters = wasted space)

FAT32 (1996)

The real revolution came with Windows 95 OSR2. FAT32 further extended the system, allowing management of disks up to 2 TB (theoretically up to 16 TB).

Main characteristics:

Smaller clusters = less wasted space

Support for long file names (up to 255 characters)

Backward compatibility with 8.3 format

Maximum volume: 2 TB (with 512-byte sectors)

Critical limit: maximum file size of 4 GB

This last limit would prove to be FAT32's Achilles heel in the modern era. A single file cannot exceed 4 GB, making it impossible to store high-definition movies, DVD disk images, or large backups.

2.4 FAT32: The Cockroach of File Systems

Despite its obvious limitations, FAT32 has shown extraordinary resilience. Nearly 30 years after its introduction, it remains the most widely used file system in the world for removable media.

Why does FAT32 survive?

The answer is one word: compatibility. FAT32 is supported by virtually every device that has ever seen the light of day:

Every version of Windows since 1996

macOS (native read and write)

Linux (full kernel support)

Smart TVs and media players

Gaming consoles (PlayStation, Xbox, Nintendo)

Car stereos and infotainment systems

Digital cameras

Routers and NAS devices

Even some printers and medical devices

When you need to transfer files between different systems without problems, FAT32 often remains the safest choice, as long as no file exceeds 4 GB.

2.5 The Limits of the FAT Era: Lessons Learned

The FAT architecture, however ingenious for its time, carried structural limitations that would become increasingly evident:

Absence of journaling

When you write a file to a FAT disk, the system first updates the data, then the allocation table. If the computer suddenly shuts down in the middle of this operation, you can end up with:

Truncated or corrupted files

Clusters marked as "in use" but not associated with any file (lost clusters)

Broken cluster chains

Anyone who lived through the Windows 98 era remembers well the dreaded "ScanDisk" at startup after a sudden shutdown, often with disastrous results for data.

No permission system

FAT has no concept of file "owner" or access permissions. Any user can read, modify, or delete any file. This makes it unsuitable for any multi-user environment or where security is important.

Fragmentation

When you create, modify, and delete files over time, data tends to scatter across the disk in non-contiguous fragments. This significantly slows access, especially on mechanical disks. "Defragmentation" was a necessary periodic ritual to maintain acceptable performance.

No data integrity protection

FAT has no mechanisms to verify that data has been written correctly or to detect silent corruption. If a bit changes due to a disk defect, the system has no way of noticing.

These limitations would drive the development of more sophisticated file systems, designed for an era of increasingly powerful and demanding computers.

3. The Era of Maturity: NTFS, ext and HFS+

3.1 NTFS: Microsoft Grows Up

With Windows NT in 1993, Microsoft had enterprise ambitions. The target audience was no longer just home users, but businesses, servers, professional workstations. FAT was clearly inadequate for this market.

The answer was NTFS (New Technology File System), a file system completely redesigned from scratch with ambitious goals:

NTFS Architecture: A New Paradigm

NTFS abandons FAT's simple architecture for a much more sophisticated system, organized around the concept of the Master File Table (MFT).

The MFT is a sort of relational database that contains information about every file and directory on the volume:

File name (native Unicode support)

Attributes (permissions, timestamps, flags)

Location of data on disk

For small files (< ~900 bytes), the data itself is stored directly in the MFT

This approach offers several advantages:

Very fast access to file metadata

Flexibility in the type of information that can be stored

Easier recovery in case of corruption

Journaling: Insurance Against Disasters

NTFS's most important feature is journaling (or "transaction logging"). Before executing any modification to file system metadata, NTFS writes a "log of intentions" in a special area of the disk.

The process works like this:

The user asks to create a new file

NTFS writes to the journal: "I'm about to create file X in directory Y"

NTFS executes the operation

NTFS marks the operation in the journal as "completed"

If the system suddenly shuts down during step 3:

On restart, NTFS reads the journal

Finds the uncompleted operation

Can either undo it (rollback) or complete it (replay)

The file system remains in a consistent state

This almost completely eliminated the corruption problem from sudden shutdowns that plagued FAT.

Integrated Security: ACL and Permissions

NTFS introduces a permission system based on Access Control Lists (ACL). Each file and directory can have detailed rules about who can:

Read the content

Write or modify

Execute (for programs)

Delete

Modify the permissions themselves

Take ownership of the object

Permissions can be assigned to:

Individual users

User groups

Special entities (like "Everyone" or "Administrators")

This system, inherited from Unix tradition but implemented independently, finally allowed Windows to be used in multi-user environments with true privilege separation.

Advanced Features

NTFS included from the start features that other file systems would only implement years later:

Transparent compression: Files can be automatically compressed, saving space without applications having to do anything special.

Encryption (EFS): Files can be encrypted with keys tied to the user account. If someone steals the disk, they cannot read the data without the correct credentials.

Hard links and junction points: Multiple "names" can refer to the same file, allowing flexible organizations without duplicating data.

Alternate data streams (ADS): A file can contain multiple "streams" of data. This little-known feature is used to store additional metadata but has also been exploited by malware to hide malicious code.

Disk quotas: Administrators can limit the space usable by each user.

NTFS Limitations

Despite its merits, NTFS has some limitations:

Cross-platform compatibility: macOS can read NTFS but cannot write to it natively. Linux requires special drivers (ntfs-3g) for writing.

Overhead: Advanced features come at a cost in terms of complexity and, in some cases, performance.

Fragmentation: Although better than FAT, NTFS can still fragment significantly over time.

No data integrity protection: Like FAT, NTFS has no checksums on data. Silent corruption is not detected.

3.2 ext2, ext3, ext4: Evolution in the Linux World

While Microsoft was developing NTFS, the Unix and then Linux world was following a parallel path with the ext (Extended File System) family.

ext2: The Foundations (1993)

ext2 (second extended file system) quickly became the standard for Linux. Designed to be fast, reliable, and with low overhead, it introduced fundamental concepts:

Inode: Each file is represented by a data structure called an "inode" that contains all metadata and pointers to data blocks

Block groups: The disk is divided into groups, each with its own inode table and allocation bitmap, improving data locality

Unix permissions: The classic owner/group/others model with read/write/execute permissions

ext2 was fast and reliable, but had a crucial problem: like FAT, it had no journaling. A crash could require a lengthy integrity check (fsck) on restart.

ext3: The Arrival of Journaling (2001)

ext3 added journaling to ext2, maintaining full backward compatibility. An ext2 volume could be "upgraded" to ext3 simply by creating the journal file, without reformatting.

Three journaling modes were available:

Journal: Both metadata and data are written to the journal before being committed. Maximum security, reduced performance.

Ordered (default): Only metadata goes to the journal, but data is written before metadata. Good compromise.

Writeback: Only metadata in the journal, data and metadata written in any order. Maximum performance, less security.

ext4: Maturity (2008)

ext4 represents the modern evolution of the family, with significant improvements:

Extents: Instead of listing each block individually, ext4 can describe contiguous ranges of blocks ("from block X to block Y"), drastically reducing overhead for large files.

Delayed allocation: The system waits as long as possible before actually allocating space on disk, allowing smarter decisions about data placement.

Journal checksum: The journal itself is protected by checksum, reducing the risk of corruption.

Volumes up to 1 EB (exabyte): Practically unlimited limits for current needs.

Nanosecond timestamps: Much greater precision for file timestamps.

Today ext4 is the default file system for most Linux distributions, used by enterprise servers, Android smartphones, and countless embedded devices.

3.3 HFS and HFS+: The Apple World

Apple has always followed an independent path. The Hierarchical File System (HFS) debuted in 1985 with the Macintosh, followed by HFS+ in 1998.

HFS+ introduced:

Unicode support for file names

Journaling (added in 2002 with Mac OS X 10.2.2)

File sizes up to 8 EB

Transparent compression

Hard links

Apple's philosophy was "elegant but closed": HFS+ worked great on Macs, but was poorly documented and difficult to support on other operating systems. Windows couldn't read it without third-party software, and Linux support was limited.

In 2017, Apple replaced HFS+ with APFS (Apple File System), designed specifically for SSDs and with modern features like native snapshots, efficient file cloning, and integrated encryption.

4. The Revolution: ZFS and the New Paradigm

4.1 Sun Microsystems and the Birth of a Giant

In 2005, while the consumer computing world was content with NTFS and ext3, something revolutionary was being born in Sun Microsystems laboratories.

Sun was a company with a legendary history in enterprise computing: creators of SPARC, Java, Solaris, and countless innovations that had shaped the industry. Their engineers asked a fundamental question: "What if we redesigned the very concept of file system, without the compromises of the past?"

The result was ZFS (originally Zettabyte File System), presented as part of Solaris 10. It wasn't simply a new file system: it was a philosophical revolution in thinking about data storage.

4.2 The Problem ZFS Solves: Bit Rot

Before understanding ZFS, we need to understand a problem that few know about: silent data corruption, sometimes called "bit rot."

Storage media aren't perfect. Over time, data can become corrupted for various reasons:

Physical defects in magnetic media or flash cells

Cosmic rays that alter single bits

Bugs in disk firmware

Errors in hardware RAID controllers

Cabling or power problems

The insidious problem is that traditional file systems don't notice. When you read a file, the system has no way to verify that the data read is exactly what was written. Corruption can go unnoticed for years, until you try to open that "safe" backup file and find it unreadable.

Studies in the enterprise sector have shown that silent corruption is much more common than thought. A famous 2007 CERN study found undetected errors in about 0.5% of files on enterprise storage systems.

4.3 The ZFS Philosophy: Trust Nothing, Verify Everything

ZFS starts from a radical assumption: trust nothing. Not the disk, not the controller, not the cable, not the RAM. Every single block of data must be verifiable.

End-to-End Checksum

Every block of data in ZFS is accompanied by a checksum (typically SHA-256 or Fletcher-4). But here's the genius: the checksum is not stored together with the data, but rather in the parent block that points to that data.

This creates a tree structure called a Merkle tree:

Data blocks have their checksum in the pointer block

That pointer block has its checksum in the level above

And so on up to the root of the file system (uberblock)

When you read a file:

ZFS reads the data block

Calculates the checksum of what it read

Compares with the stored checksum

If it doesn't match, it knows there's corruption

And here's the beauty: if you have redundancy (mirror or RAID-Z), ZFS can automatically recover the correct copy from another location. All transparently, without human intervention.

Copy-on-Write: Never Overwrite

Traditional file systems, when you modify a file, overwrite existing data. This is dangerous: if something goes wrong during writing, you can lose both the old and new versions.

ZFS uses an approach called Copy-on-Write (CoW):

New data is written to a new location on disk

Metadata is updated to point to the new data

Only when everything is successfully completed is the old space freed

This means the file system is always in a consistent state. There's never a moment when data is "halfway": you either have the complete old version, or the complete new version.

4.4 Pool Storage: Goodbye to Traditional Volumes

Another fundamental ZFS innovation is the concept of storage pool.

In traditional file systems, each disk (or partition) is a separate entity. If you have three 1 TB disks, you have three separate volumes to manage. Want to expand? You have to reformat or use complex volume management systems.

ZFS flips this paradigm:

All disks are added to a pool (zpool)

The pool appears as a single large storage space

On this pool you can create datasets (similar to directories, but with independently configurable properties)

Each dataset can have independent quotas, compression, snapshots

Want to add a disk? Add it to the pool and the space becomes immediately available. Want to replace a disk with a larger one? ZFS can do the "resilver" automatically, copying data to the new disk while the system continues to run.

4.5 RAID-Z: RAID Without Hardware Controller

ZFS includes its own redundancy system called RAID-Z, which offers different levels:

RAID-Z1: Similar to RAID-5, tolerates loss of one disk

RAID-Z2: Similar to RAID-6, tolerates loss of two disks

RAID-Z3: Tolerates loss of three disks

Mirror: Two or more identical copies of data

But RAID-Z has crucial advantages over traditional hardware RAID:

Write hole immunity: Traditional RAID-5 has a problem known as the "write hole": if the system crashes during a write, the RAID can end up in an inconsistent state. RAID-Z, thanks to copy-on-write, is immune to this problem.

Self-healing: When ZFS detects a corrupted block in a RAID-Z array, it can automatically reconstruct it from parity and rewrite the correct copy.

No proprietary controller: No expensive hardware needed. ZFS manages everything via software, and data is readable on any system that supports ZFS.

4.6 Snapshots: The Time Machine

One of ZFS's most beloved features is snapshots: instant photographs of the file system state.

Thanks to copy-on-write, creating a snapshot is practically instantaneous and takes no additional space (initially). The snapshot simply "locks" the current pointers, preventing blocks from being reused.

As data changes, the snapshot maintains references to the old blocks. You only use extra space for the differences.

Practical applications:

Incremental backups: You can send only the differences between two snapshots

Rollback: Made a mistake? Return to a previous snapshot in seconds

Clone: Create a "virtual" copy of a dataset that shares common blocks

Safe testing: Try a risky change, if it goes wrong do a rollback

4.7 ZFS in Practice: A Concrete Example

Let's imagine a real scenario: a home NAS with four 4 TB disks.

Traditional setup (without ZFS):

Buy a hardware RAID controller

Configure RAID-5 (12 TB usable, protection from 1 failure)

Create an ext4 or NTFS partition

Hope everything works

Setup with ZFS:

# Create a pool with RAID-Z1 zpool create tank raidz1 sda sdb sdc sdd # Enable transparent compression zfs set compression=lz4 tank # Create datasets for different uses zfs create tank/media zfs create tank/backup zfs create tank/documents # Configure automatic daily snapshots # (with a scheduler like sanoid)

From this moment:

Every written block is verified with checksum

Corruption is detected and corrected automatically

You can go back in time with snapshots

If a disk fails, you replace it and ZFS automatically rebuilds

If you want more space, you can replace disks with larger models one at a time

4.8 The Price of Perfection: Requirements and Considerations

ZFS is not without disadvantages:

RAM: ZFS is known for being "hungry" for memory. The rule of thumb is 1 GB of RAM for every TB of storage, plus additional RAM if you use deduplication.

License: ZFS is under the CDDL license, incompatible with Linux's GPL. This has led to legal complications and the inability to include ZFS directly in the Linux kernel (although projects like OpenZFS allow it to be used as a module).

Complexity: ZFS has many options and requires understanding to be used effectively. A configuration error can be costly.

Doesn't shrink easily: You can add disks to a pool, but removing them is difficult or impossible in some configurations.

Despite these limitations, ZFS remains the preferred choice for anyone who takes data integrity seriously: NAS, backup servers, enterprise storage, and increasingly home labs of enthusiasts.

5. The Present: The Modern File System Landscape

5.1 exFAT: The Universal Compromise

As multimedia file sizes grew, FAT32's 4 GB limit became unsustainable. Microsoft responded in 2006 with exFAT (Extended FAT).

exFAT is designed as the "FAT32 of the 21st century":

Theoretical limit of 16 EB per single file

Maximum volume of 128 PB

File names up to 255 Unicode characters

Simple and fast structure

But exFAT's real strength is compatibility:

Windows (from XP SP2 onwards)

macOS (from 10.6.5)

Linux (kernel support since 2019)

PlayStation, Xbox, Nintendo Switch

Smart TVs, cameras, action cameras

Most modern devices

exFAT has become the de facto standard for:

SD cards with capacity over 32 GB (SDXC)

USB drives for large files

External hard drives for cross-platform use

It has no journaling or advanced protection, but for removable media used to transfer files between different systems, it remains the best choice.

5.2 Btrfs: The ZFS of Linux?

Btrfs (B-tree File System, pronounced "Butter FS") was born in 2007 as an attempt to bring ZFS features to the Linux world, but with a GPL license.

It shares many concepts with ZFS:

Copy-on-write

Checksums for data and metadata

Snapshots and clones

Integrated RAID (RAID 0, 1, 10, 5, 6)

Transparent compression

Integrated volume management

Btrfs is the default file system on some distributions (like openSUSE and Fedora) and on Synology NAS devices. It's particularly appreciated for:

Easy and fast snapshots

Automatic space balancing

Ability to add and remove disks dynamically

Conversion from ext4 without reformatting

However, Btrfs has had a troubled history:

RAID 5/6 were long considered unstable (the situation is improving)

Variable performance in some workloads

Less mature than ZFS for critical enterprise storage

For desktop use and home NAS, Btrfs is an excellent choice. For mission-critical enterprise storage, many still prefer ZFS.

5.3 APFS: Apple Looks to the Future

In 2017, Apple introduced APFS (Apple File System), designed from scratch for modern needs:

Optimized for SSD: APFS is designed with NAND flash in mind, with native TRIM commands and write minimization.

Native encryption: Encryption is integrated into the file system, not an additional layer. It can encrypt individual files, entire partitions, or use multiple keys for different data.

Space sharing: Multiple volumes can share the same storage pool, dynamically allocating space as needed.

Snapshots and clones: Like ZFS and Btrfs, APFS supports instant snapshots and efficient clones.

Nanosecond timestamps: Much greater precision for timestamps, important for build systems and synchronization.

Copy-on-write for files: Copying a file doesn't physically duplicate the data, but creates references to the same blocks.

APFS is now the standard for all Apple devices: Mac, iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, Apple TV. It's a modern and capable file system, although—true to Apple tradition—completely closed and difficult to support on other platforms.

5.4 ReFS: Microsoft Responds (Sort of)

Microsoft attempted its answer to ZFS with ReFS (Resilient File System), introduced with Windows Server 2012.

ReFS includes:

Checksums for metadata (optionally for data)

Automatic error correction with Storage Spaces

No practical size limitations

Integration with Storage Spaces for redundancy

However, ReFS has had limited adoption:

Cannot be used as a boot disk (!)

Missing features like compression and deduplication in some versions

Doesn't support all NTFS features

Microsoft has limited its availability to Pro/Enterprise/Server editions

ReFS is mainly used in enterprise environments with Windows Server, but has not had the revolutionary impact of ZFS.

6. Practical Guide: Which File System for Which Situation

6.1 Quick Reference Table

SituationRecommended File SystemAlternativeNotesMulti-platformUSB driveexFATFAT32 (if < 4GB per file)Maximum compatibilityWindows system diskNTFS-RequiredmacOS system diskAPFS-Default since 2017Linux system diskext4Btrfs, XFSext4 for simplicityLinux server / NASZFSext4, BtrfsZFS for integrityEnterprise storage with WindowsReFSNTFSWith Storage SpacesCritical backups with redundancyZFSBtrfsSelf-healingSD card for cameraFAT32 or exFAT-Check manualExternal SSD for MacAPFSexFAT (cross-platform)APFS if Mac onlyLong-term archiveZFS-Verifiable integrityGaming consoleexFATFAT32Check compatibilityNetwork sharing (SMB)Any supported-Protocol abstracts FS

6.2 Scenario 1: The Home User

Profile: Uses Windows and macOS, wants to easily exchange files, saves photos, videos, documents.

Recommendation:

Windows internal disks: NTFS (already configured)

Mac internal disks: APFS (already configured)

External backup hard drive: exFAT (compatible with both)

USB drives: exFAT (or FAT32 if old devices are needed)

Bonus tip: For important backups, consider a NAS with ZFS or Btrfs. Data kept on a single disk without redundancy isn't truly safe.

6.3 Scenario 2: The Creative / Video Editor

Profile: Works with huge files (4K/8K video, Premiere/DaVinci projects), needs performance and reliability.

Recommendation:

Working SSD: APFS (Mac) or NTFS (Windows) - maximum speed

Project storage (external): exFAT if cross-platform, otherwise system native

Completed archive: ZFS on NAS with snapshots

Bonus tip: Use the 3-2-1 rule for backups: 3 copies of data, on 2 different types of media, with 1 copy offsite. For raw videos you can't recreate, ZFS with checksums is the only way to sleep soundly.

6.4 Scenario 3: The Homelab Enthusiast

Profile: Experiments with servers, VMs, containers, wants to learn but also protect data.

Recommendation:

Proxmox/TrueNAS boot drive: ext4 or ZFS

VM/data storage: ZFS (preferable) or Btrfs

Recommended setup: ZFS pool with RAID-Z1 (minimum 3 disks) or mirror (2 disks)

Practical example

# On TrueNAS SCALE or Proxmox # Pool for VMs with two disks in mirror zpool create vmpool mirror /dev/sda /dev/sdb # Pool for storage with four disks in RAID-Z1 zpool create datapool raidz1 /dev/sdc /dev/sdd /dev/sde /dev/sdf # Enable compression zfs set compression=lz4 datapool # Create datasets with automatic snapshots zfs create datapool/media zfs create datapool/backup zfs create datapool/documents

6.5 Scenario 4: The Enterprise System Administrator

Profile: Manages production servers, strict SLAs, business-critical data.

Recommendation:

Linux servers: ext4 for simplicity, ZFS/XFS for heavy storage

Windows servers: NTFS (boot), ReFS with Storage Spaces (storage)

High-performance databases: XFS or ext4 (appropriate journaling)

Backup storage: ZFS with remote replication

Considerations:

For Oracle: they often recommend ASM or specific file systems

For VMware: VMFS or vSAN

Always check vendor recommendations for the software in use

7. The Future: Trends and Innovations

7.1 Computational Storage

An emerging trend is shifting some operations from the operating system directly to the storage device. "Computational" SSDs can perform operations such as:

Compression/decompression

Encryption/decryption

Search and indexing

Database operations

This will require file systems that can intelligently delegate operations to the device.

7.2 Non-Volatile Persistent Storage

Technologies like Intel Optane (now discontinued) and future persistent memories blur the boundary between storage and RAM. File systems like NOVA and PMFS are designed specifically for these new paradigms, where access to persistent data can be almost as fast as RAM access.

7.3 Distributed File Systems

With cloud computing, more and more storage is distributed across multiple physical machines. File systems like:

Ceph: Open source distributed storage

GlusterFS: Scalable file system

HDFS: For big data (Hadoop)

S3: Object storage (not strictly a file system)

are becoming increasingly important for massive scales.

7.4 Integrity as Standard

The ZFS lesson is permeating the entire industry. More and more file systems are implementing checksums and integrity checks. It's possible that in the future verifiable integrity will become a standard feature, not an exception.

8. Conclusion: Never Underestimate the Fundamentals

8.1 Lessons Learned

This journey through file system history teaches us several lessons:

Simplicity has a cost: FAT32 survives because of its simplicity, but pays for it with limitations that in 2024 seem anachronistic. Sometimes "works everywhere" is worth more than technical perfection.

Data integrity isn't guaranteed: For decades we built storage systems that couldn't verify if data was corrupted. ZFS showed that we can do better, and this lesson is influencing the entire industry.

Evolution is continuous: From floppy disks to NVMe SSDs, from KB to PB, file systems have constantly evolved to adapt to new technologies and new needs. This evolution will continue.

The right choice depends on context: There is no "best" file system in absolute terms. The choice depends on your specific needs: compatibility, performance, reliability, simplicity.

8.2 The Value of the Invisible

File systems are the epitome of invisible technology: when they work, you don't notice them. But the next time you save a document, copy a photo, or back up your data, think for a moment about the complex system working under the hood.

Every file you've ever saved, every vacation photo, every work document, every creative project—everything exists thanks to these elegant data structures that organize binary chaos into usable information.

And when you choose how to format that new external drive, or how to configure your NAS, remember: that choice could make the difference between "I lost everything" and "the system automatically recovered."

Choose wisely. Your data will thank you.

Do you have specific questions about a file system or particular situation? Want to explore some technical aspect? Comments are open for discussion.

Bibliography: